Nonfiction

eBook

Details

PUBLISHED

Made available through hoopla

DESCRIPTION

1 online resource

ISBN/ISSN

LANGUAGE

NOTES

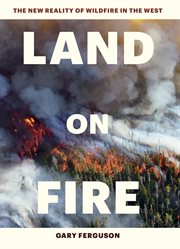

"This comprehensive book offers a fascinating overview of how those fires are fought, and some conversation-starters for how we might reimagine our relationship with the woods." -Bill McKibben, author of Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet Wildfire season is burning longer and hotter, affecting more and more people, especially in the west. Land on Fire explores the fascinating science behind this phenomenon and the ongoing research to find a solution. This gripping narrative details how years of fire suppression and chronic drought have combined to make the situation so dire. Award-winning nature writer Gary Ferguson brings to life the extraordinary efforts of those responsible for fighting wildfires, and deftly explains how nature reacts in the aftermath of flames. Dramatic photographs reveal the terror and beauty of fire, as well as the staggering effect it has on the landscape. We are living in the age of wildfire-it is changing the land, the economy, the welfare of wildlife, and the livability of the American West. Land on Fire explores the science behind wildfire and what is being done to control it. Gary Ferguson has written many books on nature and science including Hawks Rest, the first nonfiction work to win both the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Award and the Mountains and Plains Booksellers Award for Nonfiction, Decade of the Wolf, The Great Divide, and The Carry Home. His articles have appeared in Vanity Fair, the Los Angeles Times, and other publications. His lectures on wilderness are a culmination of 30 years researching-and experiencing-the marriage of wild lands, history, myth, and narrative psychology. Visit him at wildwords.net. Prologue Across my thirty-five years of writing about the natural and cultural history of the American West-logging nearly a quarter million miles of highway and some 30,000 miles of trail along the way-wildfire has been a common companion. I've seen its handiwork all around my longtime home in southern Montana; how it's driven new generations of aspen and lodgepole forests in the Beartooth Mountains; and farther to the south, in the outback of Yellowstone, the way it's cleaned and pruned the Douglas-fir and Engelmann spruce forests. Flames at my back have sent me scurrying like a startled mouse out of the lonely folds of Hells Canyon, while big burns have eaten beyond recognition some of the landscapes I roamed in my youth: slices of the Sawtooth Mountains of Idaho, the Weminuche Wilderness of Colorado, the southern uplands of Utah. When I first came to the West as a young man in the late 1970s, wildfire was still seen largely as a destructive force, which of course at times it can still seem today. But across the decades I've also come to know it as a powerful agent of healing, a mighty wand that wipes the land free of disease and insects and fallen timber to create a stage for healthy, altogether magnificent new flushes of life. By returning essential nutrients to the soil, fire allows a flush of grasses that can provide especially nutritious graze for elk and bison, not to mention food for dozens of species of groundforaging birds. At the same time, small mammals who feed on the seeds of those grasses tend to increase in number after a burn, in turn providing food for hawks, owls, coyotes, and the like. Lately, though, I've also been witness to this land changing, increasingly being wrung dry by severe episodes of drought. And as a consequence, wildfire is establishing itself as a far bigger, much more forceful presence than ever before. In many recent years my neighbors and I have choked on smoke from burning forests, have turned our heads up to the August sky looking for rain until our necks hurt, and on several occasions have packed up a few precious belongings and evacuated our homes, hearts in our throats, in the face of advancing f

Mode of access: World Wide Web