Details

PUBLISHED

Made available through hoopla

DESCRIPTION

1 online resource

ISBN/ISSN

LANGUAGE

NOTES

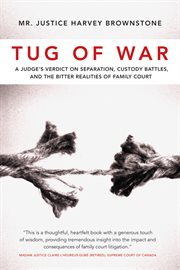

Tug of War is the first book of its kind. Written by a sitting family court judge in layman's language, it demystifies complex family law concepts and procedures, clearly explains how family court works, and gives parents essential alternatives to resolve their own custody battles and keep their kids out of the often damaging court system. Breakup rates in North America are skyrocketing. Recent statistics say 45% of marriages end in divorce, and at the centre are countless children, thrust by their families into a complex and seemingly impermeable family court system. Tug of War explains the role of lawyers and judges in the family justice system, and examines the parents' own responsibilities to ensure that post-separation conflicts are resolved with minimal damage to the children stuck in the middle of parental disputes. Justice Harvey Brownstone explores themes that apply to all families and parents in conflict. He draws on fourteen years sitting on the family court bench to provide clear case examples with inclusive and accessible language. Tug of War describes alternatives to litigation and exposes the myth that parents can represent themselves without a lawyer in family court. Justice Brownstone discloses the inner struggles of parents, judges and lawyers in the maelstrom of marital conflict. This book is a must-read for couples involved in or contemplating separation, family law judges, lawyers, mediators, parenting coaches, psychologists, family counselors, social workers, students and professors of family law at law schools. It is endorsed by judges currently sitting in Ontario and New York State. Mr. Justice Harvey Brownstone currently presides at the North Toronto Family Court. He was appointed a provincial judge in 1995, after serving as Director of the Support and Custody Enforcement Program of the Ministry of the Attorney General (now the Family Responsibility Office). He received his LL.B. from Queen's University in 1980, and after working as a full-time Legal Aid duty counsel in the criminal courts, he joined the Legal Aid research facility, focusing primarily on Family Law. After more than fourteen years of presiding in family court, one question has never ceased to amaze me: how can two parents who love their child allow a total stranger to make crucial decisions about their child's living arrangements, health, education, extracurricular activities, vacation time, and degree of contact with each parent? This question becomes even more mind-boggling when one considers that the stranger making the decisions is a judge, whose formal training is in the law, not in family relations, child development, social work, or psychology. Now add the fact that, because of heavy caseloads and crowded dockets, most judges have to make numerous child custody, access, matrimonial property, and support decisions every day on the basis of incomplete, subjective, and highly emotional written evidence (called affidavits), with virtually no time to get to know the parents and no opportunity to meet the child whose life is being so profoundly affected. What person in their right mind would advocate for this method of resolving parental conflicts flowing from family breakdown? These are some of the questions that family court judges agonize over. Some say the answers are complicated and have much to do with social conditioning, economic class, levels of education, sophistication, familiarity with community resources, and even culture. I say the answers are simple. The institution of marriage has not been a great success in North America. The United States has the highest divorce rate in the western world, followed by the United Kingdom and Canada.1 Moreover, divorce statistics do not take into account couples who lived in common-law (unmarried) relationships and broke up

Mode of access: World Wide Web